Out of bounds

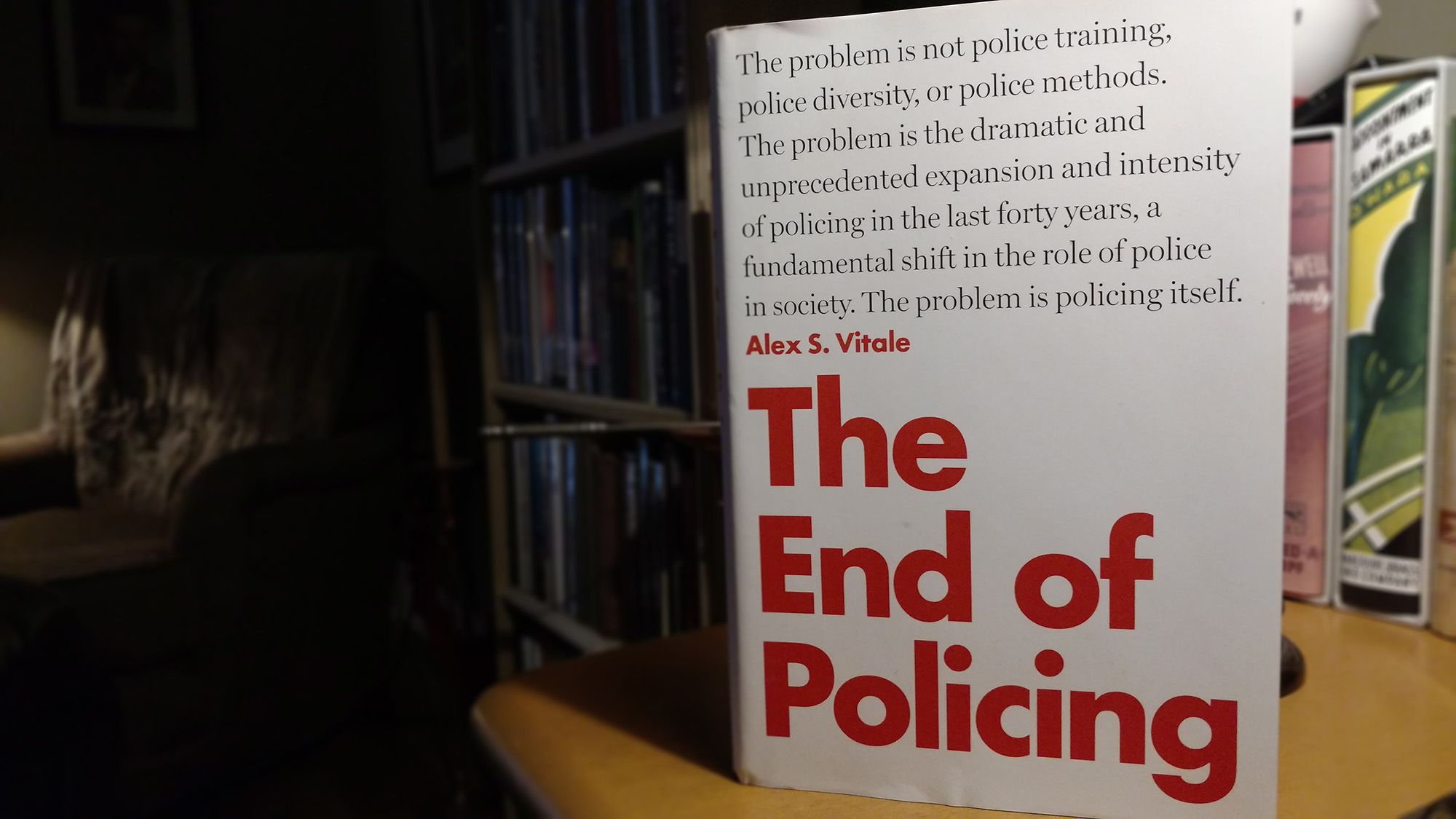

“The myth of policing in a liberal democracy is that the police exist to prevent political activity that crosses the line into criminal activity, such as property destruction and violence. But they have always focused on detecting and disrupting movements that threaten the economic and political status quo, regardless of the presence of criminality. While on a few occasions this has included actions against the far right, it has overwhelmingly focused on the left, especially those movements tied to workers and racial minorities and those challenging American foreign policy.” — Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (2017, Verso)

“The myth of policing in a liberal democracy is that the police exist to prevent political activity that crosses the line into criminal activity, such as property destruction and violence. But they have always focused on detecting and disrupting movements that threaten the economic and political status quo, regardless of the presence of criminality. While on a few occasions this has included actions against the far right, it has overwhelmingly focused on the left, especially those movements tied to workers and racial minorities and those challenging American foreign policy.” — Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (2017, Verso)

I’ve written about this before — see related blog posts below — so my loveless relationship with state authority, especially coercive state authority, is a matter of public record. From the Haymarket affair to the Ludlow massacre to the Sacco and Vanzetti show trial to the Palmer raids to the bald-faced murder of Black Panther and establishment bête noire Fred Hampton, law enforcement has been acting in collaboration with and often at the explicit behest of elite interests since long before Allan Pinkerton was a twinkle in his daddy’s eye.

With the rise of for-profit prisons and offender monitoring services, the nominal separation of those interests from the “public servants” they direct has all but disappeared. Prison-industrial juggernauts like Sentinel and Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) command an army of lobbyists who write the very laws that keep them in business.

In The End of Policing, Brooklyn College sociology professor Alex Vitale argues that many now traditional law enforcement functions (the “war on drugs,” sex work interdiction, border patrol, suppression of civil protest, school “resource officers,” etc.) are inefficient or altogether inappropriate means to stated ends.

He believes that homelessness and drug abuse, for example, should be addressed by social workers and medical professionals, and that drugs themselves should be decriminalized and regulated, as should sex work. Borders should be open and the human rights of immigrant workers, rather than the financial interests of employers, should be given priority. Police presence should not be normalized in schools, and social activists, organizers, and others involved in protest movements should be treated as citizens exercising their First Amendment rights, not as terrorists.

Some portion of the billions of dollars spent each year on policing and incarceration, Vitale suggests, might be better spent rebuilding underserved communities. Adequate long-term housing, improved healthcare and education, living wage employment, and meaningful professional counseling would diminish incentives to criminality and drug abuse, obviating the need for criminal justice solutions.