Features cat

“Features cat” isn’t an attribute we see mentioned with any regularity – never, that I’m aware of – in publishers’ catalogs or library databases. Not where books intended for adult readers are concerned. We exclude for purposes of this conversation the kittens-with-mittens subgenre.

“Features cat” isn’t an attribute we see mentioned with any regularity – never, that I’m aware of – in publishers’ catalogs or library databases. Not where books intended for adult readers are concerned. We exclude for purposes of this conversation the kittens-with-mittens subgenre.

Google “cats in literature,” and you’ll find the Cheshire Cat, of course, which qualifies. You’ll find Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, too, which qualifies, but with reservations, partly because it’s poetry, partly because “rum tum tugger” sounds like Shirley Temple talking to Mr. Bojangles, and partly because the book spawned an adaptation that I detest. (Did you know that “Cats” is the longest running Broadway musical in Hell? Fact.) There’s also Hermione’s cat in the Harry Potter series, which I have to admit I’d forgotten about until just now, and which I’m allowing mainly because it’s hard to categorize as children’s literature a seven-book series that’s cumulatively twice as long as Atlas Shrugged.

But none of these, with apologies to Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, are hitting the mark for grownup, non-fantasy-fan cat fanciers seeking book-length prose that features cats.

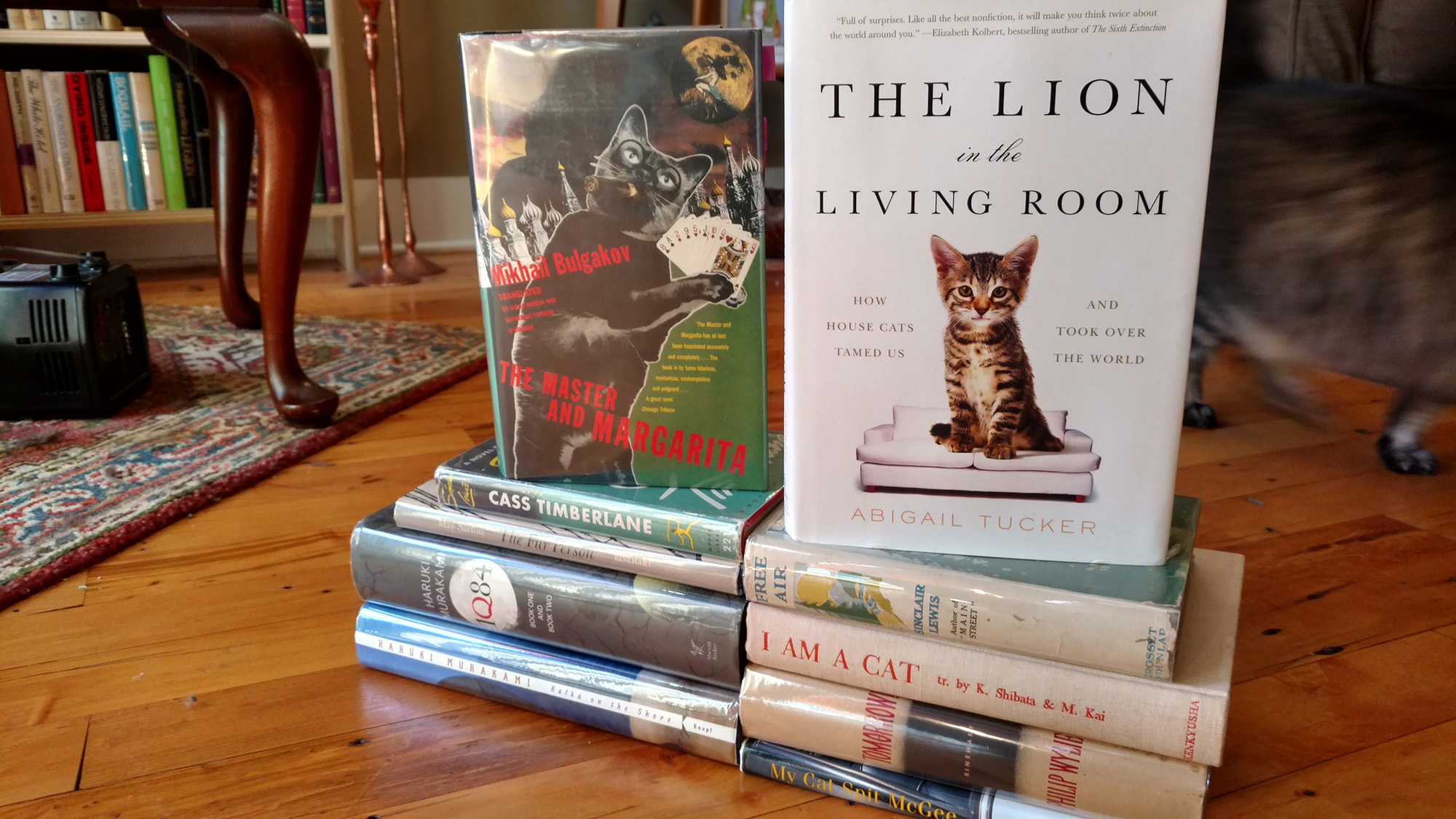

So if I may, here in no particular order are a few to consider:

- Tomorrow by Philip Wylie (1954, Rinehart): Wylie dedicated this pre/post-nuclear-apocalypse tale of Middle America to the Civil Defense Corps, so I file it under Cold War era/post-apocalypse/science fiction. The citizens of Green Prairie and River City learn the hard way that disaster preparedness is serious business. Fairly flag-wavy, but not as bad as Heinlein, and taken on its own terms, surprisingly affecting. Plenty of well-rounded characters, one of whom is Queenie, the tomcat. (372 pages)

(Spoiler: Queenie does not die. In fact, the last lines of the book are these: “The sun went down and left the lawn in gilded light. Queenie yawned — and touched his mouth delicately.”) - Cass Timberlane by Sinclair Lewis (1945, Random House): A thoroughly unromanticized study of modern marriage, and though less bare-knuckled in this regard than John O’Hara’s Appointment in Samarra, it’s fairly gritty for its day. The modern Library edition of Cass Timberlane is 390 pages long, and Cleo arrives as a kitten at the top of page 15. She makes frequent appearances throughout the book, is doted on by Jinny Timberlane, Cass Timberlane’s wife, and cat references and iconography abound, becoming a theme of continuity. Cass thinks of Jinny as having the movements and personality of a cat. (390 pages)

(Spoiler: On page 374, adult Cleo is killed by dogs, and Jinny is devastated. The Timberlanes’ marriage has fallen apart and Jinny is on the verge of death herself, but she and Cass begin a reconciliation that culminates on page 388 when the faithful maid places a mysterious pink tea cozy on the dinner table after the evening meal has been cleared away. Underneath it, Cass and Jinny discover a tiny black kitten, the one from Cleo’s last litter that looks exactly like her, and whom they name Cleo, not in Cleo’s honor, but because they sense the kitten is Cleo reincarnated. So yes, Cleo dies, but we forgive this – albeit reluctantly – because she triumphs o’er the tomb, and because her death/transfiguration is such a skillfully wrought metaphor.) - Free Air by Sinclair Lewis (1919, Harcourt): A sentimental tale of first love and class consciousness on the open road circa Woodrow Wilson. Protagonist Milt Dagget’s traveling companion is Lady Vere de Vere, a scruffy stray whose decision to accompany him is as spur-of-the-moment (and please note I resisted the temptation to say “purr-of-the-moment”) as Dagget’s decision to leave Gopher Prairie. Dagget’s paramour is Claire Boltwood, a young lady of considerable means, who is traveling to Seattle with her father some miles ahead. Various car problems bring them together — Dagget is an expert mechanic — and the bulk of the novel concerns their attempts to span the considerable wealth gap that divides them. (370 pages)

(Spoiler: Lady Vere de Vere is killed by a bear just as Milt makes his move on Claire, at which point it becomes obvious that Lewis has used Lady Vere de Vere as a “things of childhood” placeholder for Milt’s first adult relationship. Moreover, her death now serves as an opportunity for the young couple to bond in the face of tragedy. We frown on such devices.) - The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (1997, Picador, Burgin trans.): This is one of my favorite books of any genre, and it’s little wonder the character of Behemoth is celebrated worldwide. Here he’s discovered in the home of the late Mikhail Alexandrovich Berlioz: “But worse things were to be found in the bedroom: on the jeweler’s wife’s ottoman, in a casual pose, sprawled a third party – namely, a black cat of uncanny size, with a glass of vodka in one paw and a fork, on which he had managed to spear a pickled mushroom, in the other.” (M&M isn’t fantasy, by the way, at least not as I think of the genre. It’s magical realism.) (335 pages, plus commentary)

- I Am a Cat by Natsume Soseki (1961, Kenkyusha, Shibata trans.): Originally published in Japan in 1906, this oddity is narrated by a nameless cat adopted by a feckless and self-absorbed schoolteacher. The schoolteacher’s equally feckless and self-absorbed acquaintances visit him in his home to chatter nonsensically. No plot, no sympathetic or believable characters. Vapid, childlike humor. What might have been risqué or politically dangerous during the Russo-Japanese War now seems merely silly. Historical interest derives from glimpses of Japanese society … dress, food, customs, etc. … and Japanese resentment of Western influences. The narrator is not treated well, however, which is a serious concern. He is kicked and manhandled, but he accepts this treatment stoically as fair exchange for shelter. (431 pages)

(Spoiler: On the final page, drunk on leftover beer, the narrator drowns in a rain barrel, praising the Buddha as life slips away. Hard to recommend.) - Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami (2005, Knopf): My introduction to magical realism and the reason I went on to read almost all of Murakami’s other books. Beguiling, transporting, startling, disturbing, and beautiful. And UFOs. And a few people blessed with the ability to carry on perfectly normal conversations with cats. (436 pages)

- IQ84 by Haruki Murakami (2009-11, Harvill): More magical realism and somewhat over-long, but included because the central character visits a parallel-reality Town of Cats. (987 pages in three volumes)

- The Fur Person by May Sarton (1957, Rinehart): A fictionalized account of the author’s relationship with a wayward tomcat. If there’s a “hey, but that’s a kid’s book!” listed here, this would be it, although it’s equally sure to charm the adult ailurophile. (106 pages)

- My Cat Spit McGee by Willie Morris (1999, Random House): Non-fiction. Morris, a self-described dog person and former cat hater, loves Spit McGee with a manly ardour that passeth all understanding. Unless you’re a cat person, in which case it makes total sense. Deeply moving, so open your heart. I cried like a little girl. (141 pages)

(Spoiler: Spit does not die.) - The Lion In the Living Room by Abigail Tucker (2016, Simon & Schuster): Non-fiction. A fascinating overview of the history, habits, physiognomy, and social significance of cats. Written with respect and affection, but may be too clinical for folks who prefer to think of cats as lazy clowns. The author gives us instead “fully-loaded predators.” Says Tucker on p. 177, “Communication is not their forte, and they don’t really have complications or denouements. They are agents of utter stillness, or acute violence.” (187 pages, plus notes)

- A Cat, a Man, and Two Women by Jun-ichiro Tanizaki (1990, Kodansha International): An unlikely Lothario finds his relationships with two women greatly affected by their relationship with a cat. “Cats have a wisdom of their own – they understand at once how someone feels about them.” (p. 69) A bit too silly in parts for my taste – that incongruously juvenile brand of silliness that I associate with Japanese fiction – but engaging overall. (164 pages)

- If Cats Disappeared from the World by Genki Kawamura (2019 Flatiron Books): The Devil visits a dying man to make him an offer he can’t refuse … or can he? This one involves cats. “Life must mean something to everything, even a jellyfish or a pebble by the side of the road.” (p. 67) A gently wise and charming read. (168 pages)

- The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide (2001 New Directions): A young couple is adopted by a neighbor’s cat. “Odd how you still refer to her as a ‘guest’ despite having become so attached.” (p. 55) Poignant, thoughtful, engaging. Cat as implicit visitor from the spirit realm. (140 pages)

- The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa (2018 Berkeley): A postal worker discovers he has only a short time to live and, though deeply conflicted about doing so, immediately sets about trying to find a new home for his beloved cat. “With a cat hanging around the house, a cat with a hooked tail to gather in pieces of happiness, maybe they’d be able to live a simpler, more innocent life.” (p. 20) An absolutely gorgeous novel. Made me cry. Repeatedly. (277 pages)

- The Cat and the Coffee Drinkers by Max Steele (1969 Harper & Row): Ms. Effie Barr runs an eclectic finishing school of sorts for kindergarteners in her stately old home. Acquiring a taste for black coffee is part of the curriculum. So is (Spoiler) how best to euthanize the class cat after he’s been hit by a car and then mauled by dogs. (Hint: You roll him up in a chloroform-soaked rug, put the rug in a darkened tool shed, and wait.) A weird little novella (a short story in book form, really), charming at first, but ultimately, and I’d argue pointlessly, disturbing. (42 pages)